reviews

reviews

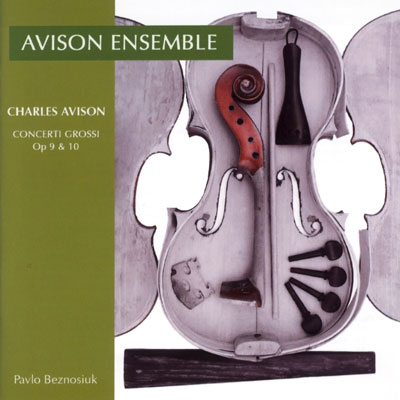

Charles Avison

Concerti Grossi Opus 9 and 10

The Avison Ensemble

Pavlo Beznosiuk (director & violin)

2 CDs on Divine Arts, dda 21211

• Classic FM Disc of the Week, 24 August 2008 •

• World premiere recording •

Classic FM Magazine

'The concerti tumble out like pristine toys from a long-locked cupboard.'

Rick Jones

The period instrument Avison Ensemble exists to perform the music of the forgotten English composer Charles Avison of whose works these two CDs of charming concerti grossi are but a small proportion. For a long time he was known for a popular organ piece Sound the Loud Timbrel, a gentle pastoral included here in the Concerto in B flat, op. 9 no. 8.

The ensemble performs it with simplicity, freshness and lovingly tended, authentic ornaments sighing into cadences. The concerti tumble out like pristine toys from a long-locked cupboard. Pavlo Beznosiuk leads with a decisive bow that seems to sing ‘injustice' for Avison's inexplicable neglect.

The Daily Telegraph

'The ensemble does its composer proud in a stylish series of sturdy allegros, graceful largos and delicate, attractive arias.'

Anna Picard

Forgotten for two centuries, the music of Newcastle's premier composer, concert organiser and essayist Charles Avison (1709-1770) has enjoyed a remarkable renaissance since cellist Gordon Dixon found a bundle of his scores hidden in a cupboard and formed the Avison Ensemble. The fifth recording in the group's series of discs devoted to music from the North-east, Avison's Opus 9 and Opus 10 'Concerti Grossi' are sweetly melodic, succinct and conservative. Led by Pavlo Beznosuik, the ensemble does its composer proud in a stylish series of sturdy allegros, graceful largos and delicate, attractive arias.

Audiophile Audition (USA)

'It is hard to see how these concertos could be better played than they are here.'

Mike Birman

The music of the 18th century English composer Charles Avison was heavily indebted to Archangelo Corelli, whose seminal Op. 6 concertos were phenomenally popular throughout Europe and were widely disseminated and easily accessible for performance as well as study. Corelli was the composer most responsible for the development of the concerto grosso form which assumed its popularity at the beginning of the 18th century. Notable composers adopting the form were Vivaldi, Handel and Bach, thus insuring its preeminence.

Avison modeled his concertos on those by Corelli, preferring the four-movement 'sonata da chiesa' or church sonata paradigm. This type of sonata, as distinct from the 'sonata da camera ' or chamber sonata, generally consists of four movements. They often use more than a single melody and the movements are ordered slow-fast-slow-fast with respect to their tempo. The second movement is usually a fugal allegro, and the third and fourth movements are binary forms that occasionally resemble the dances the sarabande and gigue. This gives this type of sonata some of the aspects of the Baroque suite.

Avison spent most of his career in Newcastle which became wealthy enough on the back of the coal industry to become a significant cultural center. By the time he composed these late concertos during the period 1766-1769 he had standardized his compositional style into a formulaic pattern. The new galant style was already far along in the process of conquering the European musical world but Avison rejected the current state of music, insisting on a return to the earlier concerto grosso. Despite this approach the concertos are utterly delightful for their serene beauty and melodic invention. They possess those Apollonian qualities that we think of when we contemplate the 18th century in England: the well-ordered artistic world of Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift and Richard Brinsley Sheridan.

It is interesting to consider that most of Avison's work was little known until cellist Gordon Dixon discovered a collection of 18th century music hidden away at the back of a cupboard. Mr. Dixon formed The Avison Ensemble with the intention of popularizing the composer's music as well as other neglected British composers of the era. The Avison Ensemble perform on period instruments and have added still more works to the English Baroque repertoire by recently acquiring two of Avison's original workbooks which contain unpublished works by Avison and other 18th century composers. Led by early music specialist Pavlo Beznosiuk they play this music with the necessary phrasing, tempi and stylistic rightness that brings this music to life. There is not a hint of the museum quality that can afflict little-known music for which a strong performance tradition does not as yet exist when it suddenly sees the light of day. This music seems to breathe naturally and is utterly charming in all respects. It is hard to see how these concertos could be better played than they are here.

The sound quality is rich and reverberant, perfectly complementing the strings. The sound field is wide enough to suggest a mid-sized hall. The contrapuntal lines of the music are clearly distinguishable making it easy to appreciate Avison's superb skill.

The Consort

'The overall exuberance of the performance and the quality of the ensemble is utterly winning ... this double-CD set is a mine of varied and exciting music.'

Caroline Ritchie

Given the international climate of today's early music scene, it is quite reassuring to encounter an English group like the Avison Ensemble. Formed in response to the discovery (by cellist Gordon Dixon) of a number of concertos by the Newcastle-born composer Charles Avison (1709-70), the ensemble focuses on the music of Avison and his contemporaries, and keeps its roots in Avison's native northwest of England. Under the direction of violinist Pavlo Beznosiuk, and through several years of performing and recording Avison's music, the group has developed a distinct ‘house style' that truly sparkles in this recording.

An important writer on music, and a driving force behind concert life in the northwest, between 1740 and 1769 Avison published seven sets of concertos. Based on the Corellian model, and showing the influence of Avison's teacher, Geminiani, Avison's music is at once exuberant and stylish, avoiding the ‘rapid style of composition now in vogue' in favour of ‘the native Charms of Melody' and ‘the nobler Powers of Harmony'. This quotation, a critique of the contemporary galant idiom from the preface to the op.9 concerti, perhaps underestimates the composer's own force of invention. Avison's writing is indeed Italianate, but hugely varied, with highly dramatic moments (the D minor concerti from op.10 stand out here), Handelian grandeur (the E flat concerto from op.10 and C major from op.9), and Corellian simplicity (the F major from op.10).

Avison's awareness, and use, of key colour is striking – the C major concerti have a very different character from the F major, and the G minor from the D minor, for example. I would be interested to know whether this was a feature of the composer's theoretical writings – it certainly brings an impressive degree of variety to the disc.

The Avison Ensemble's sound is warm, with a beautifully unified legato among the upper strings. The texture is thick, with a satisfyingly strong presence from the inner parts, so often the bearer of interesting lines in this music. The bass section is powerful without being overpowering, really coming to the fore in moments such as the dramatic interjections in the Largo of op.9 no.3. I occasionally miss a more plaintive texture in some of the affective slow movements, but the overall exuberance of the performance and the quality of the ensemble is utterly winning. Although Simon Fleming's excellent programme notes describe the op.6 concerti as ‘Avison's pinnacle', the op. 9 and 10 have much to recommend them, and this double-CD set is a mine of varied and exciting music.

Midwest Record

'Warmly played in period fashion with great attention to detail, this is one of those special treats it's better to just enjoy.'

Chris Spector

Oddly enough, even in this day and age, there's classical music by composers that has still been unrecorded and basically undiscovered. Avison Ensemble specializes in early classical work and highlights Avison heavily as evidenced by this new release in this successful series. World premiere recordings of works created in the last years of his life, it a delightful find for those jaded ears that are thinking there's nothing new under the classical sun to be found. Warmly played in period fashion with great attention to detail, this is one of those special treats it's better to just enjoy than pick apart.

BBC Music Magazine

George Pratt (Joint review with dda21213)

Charles Avison (1709-70) unusually made a considerable name for himself outside London – as writer, composer, concert promoter and organist. Although he spent time in the capital as a pupil of Geminiani, he returned to his birthplace, Newcastle, for the rest of his working life.

Avison wrote no less than seven full sets of concertos, choosing the older style and formal structure of Corelli and Geminiani – four movements and a trio of soloists – rather than the gallant Vivaldian three-movement model with virtuoso solos. As the basis of his 1744 set, he took the keyboard studies of Domenico Scarlatti, transcribing them into 12 effective orchestral concertos. We have Avison to thank for preserving ten of Scarlatti's movements, otherwise unknown. They are substantial pieces, earning lively and sensitive playing from the Ensemble's 11 strings and continuo. Scarlatti's invention makes them distinctive, and often memorable – the poignant opening of No. 3, the Con furia in No. 6 elicits some powerful playing especially from leader Pavlo Beznosiuk.

The later sets here are less striking and three-to-a-part upper strings have occasional raw movements. A pity, perhaps, that the Ensemble didn't take up Avison's commercially-inventive options: he described them as suitable for orchestra, or quarter or even solo harpsichord, to vary the textures. The over-riding impression after hearing 71 brief movements, many under a minute long, is of urbane charm, fluent melody and purposeful harmony, but no one concerto imprints itself on the memory for long. They are nonetheless attractive, now, as they were for audiences at Avison's regular subscription concerts in the Newcastle Assembly Rooms.

American Record Guide

'Beznosiuk gives these concertos excellent treatment. Sound is very good. This is a high-quality recording of some obscure music.'

Crawford

Here is Pavlo Beznosiuk's latest entry in his project to record all of the published – and some of the unpublished – music of Charles Avison. He has already done two sets of Avison's violin concertos for Naxos, the Opus 3 and 4 concertos and the Opus 6. The concertos on this new release seem not available in any other recording, and even Avison's 12 concertos after Domenico Scarlatti are available in only two recordings.

A great deal of interest was stimulated in Avison a few years ago when a good-sized stash of his music was discovered in the back of a cupboard in an English house. Gordon Dixon, who made the discovery, then founded the Avison Ensemble to take up the work of the neglected British composer.

Avison, fairly well known in the 18 th Century, is not first-rate – and I don't suppose anyone pretends that he is. Nonetheless, his work is fresh and listenable, and the effort to record his music is entirely worthy. The 12 concertos of Opus 9 were originally published in two sets of six, the first appearing in 1766 and the second in 1767. Avison intended them to be flexible; they could be performed on a variety of instruments as solo keyboard pieces or as quartets. Corelli is the biggest influence; they are composed with the Corellian four movements rather than the Vivaldian three.

Beznosiuk probably needs no introduction to collectors of early music, as he has been active in various early music groups for a long time, most notably with the Academy of Ancient Music, the Hanover Band, and the Parley of Instruments. He gives these concertos excellent treatment. Sound is very good. This is a high-quality recording of some obscure music.

Classical Source

'These are exceptionally stylish 'period' performances and are ideal ambassadors for the promotion of this neglected composer.'

Antony Hodgson

The Concerto grosso has a long and respectable reputation as a musical genre and Simon D. I. Fleming's booklet note very properly describes the nature of the music, pointing out the durability of this type of composition. I found his reminder that Concerti grossi were still being published as late as the nineteenth-century to be somewhat intriguing.

I suppose the first name to spring to mind when the term Concerto grosso is used would be Handel, but although Charles Avison (1709-1770) was barely a generation younger, there is little resemblance to the style of the great Anglo-German master – indeed even the earliest of the works in this set (the first half dozen of Opus 9) were not composed until six or seven years after Handel's death.

At this time music was changing, Haydn was writing his early symphonies and music was flourishing in European courts. At Mannheim for example the so-called 'classical' style flourished relatively early but, by contrast, Avison is sometimes said (both in Fleming's notes and by other commentators) to have been influenced by Corelli – born half a century earlier. On first hearing these works I caught elements of Geminiani – a pupil of Corelli – and it has been surmised that Avison could also have been Geminiani's pupil.

None of this seems to have lead to any great advancement of style; it seems that the Baroque format sufficed for Avison. True the melodies are less Baroque than those of Handel but they do not seem to advance much further than those of, say, Avison's exact contemporary John Stanley (who was born in 1712). Another reason could be that Avison lived and died in Newcastle and perhaps because of the increasing importance of that (then) town he felt no great need to involve himself in the lively musical life of London where new musical styles were beginning to evolve.

Within the generous ration of concerti provided in these two sets of opus numbers it is difficult to detect any great difference in style between the earlier and the later compositions. Basically the normal slow-fast-slow-fast pattern of the Concerto grosso is held-to although there are three exceptions: the F major work from Opus 9 has a central Fugue and a final Aria; the Fourth of the Opus 10 set has five movements – the final rapid 'Gavot' sounding rather like a classical Allegro of a later period – in fact this movement is unlike any other in the whole set; and the following work has just three movements.

In terms of performance, the Avison Ensemble is superbly unified. Not surprisingly, several other of its recordings are mentioned in Divine Art's very well presented annotation. Pavlo Beznosiuk leads with confidence – he is not afraid to add occasional decorations but these are not intrusive and never interrupt the melodic line. In all, these are exceptionally stylish 'period' performances by musicians in-tune with Avison's philosophy and are ideal ambassadors for the promotion of this neglected composer. Divine Art must be commended for promoting rarely heard 18th-century composers, an admirable activity but it can involve commercial risk.

The nature of the recording influences the impression given by the music itself. The acoustic of the venue is very suitable, the string quality has attractive warmth and there is no undue highlighting of the leader. The eleven players sound full-bodied but after a while I became concerned about the narrow dynamic range, which seems to stay entirely between mezzo piano and mezzo forte ; add to this the harpsichord being buried deeply within the texture and an element of sameness begins to develop. Harpsichord continuo should enrich bass harmonies but because the tone of this instrument is lacking in treble, apart from a very occasional improvisatory link, the ear picks up no more than a slight colouring of the main notes of the bass line.

I realise that nowadays engineers tend to play down the presence of the harpsichord (I look back nostalgically to the sparkling quality achieved by the Nonesuch engineers in the 1960s) and perhaps I am being ungrateful in view of the comfortable and beautiful recorded quality provided here, but I fear that in the context of Avison's attractive but perhaps modest talent, it puts the works in danger of seeming too similar to one another.

MusicWeb

'These are excellent performances ... I found myself suffering from an excess of good things.'

Brian Wilson

Two apologies are due, first to Avison himself and then to his eponymous ensemble. When I first encountered his music, on an early Academy of St Martin's recording of an anthology of eighteenth-century music on Oiseau-Lyre, later reissued on Decca Ace of Diamonds, I thought he was French: try pronouncing it as if it were a French name – it works. I knew that he had worked in Newcastle and Durham but, with the typical arrogance of one who escaped from the North to study at Oxford and then to live in London, I assumed that no good thing could come out of eighteenth-century England, das Land ohne Musik , let alone Newcastle. Sincere apologies to all those in the North East; I soon discovered my error.

Secondly, though I have heard the Avison Ensemble on BBC Radio 3, I hadn't realised what an accomplished and professional group they are – I'd thought of them as very talented amateurs.

The Avison Ensemble have already recorded the music of their namesake for Naxos and Divine Art. Their 2-CD recording of the Concerti Grossi, Op. 6 on Naxos 8.557553-4 was welcomed by Jonathan Woolf and Johan van Veen as doing Avison proud. Robert Hugill was equally appreciative of their later recording of Opp. 3 and 4 (8.557905-6).

Having switched to the Divine Art label, the Ensemble recently recorded the newly-discovered set of Concertos after Geminiani's Op.1, not to be confused with his re-workings of Scarlatti, to the satisfaction of JV again, though he had some reservations about the recorded sound – (DDA21210). Divine Art already have a recording of some of the Op.9 concertos in their catalogue, performed in the alternative scaled-down versions by The Georgian Ensemble (24108), performances which David Wright thought a little lacking in spirit in the faster music. I think DW would have found what he was looking for in these Avison Ensemble recordings of the complete Op.9 and Op.10.

Let me get one grumble out of the way first. I thought I was the only person to notice the growing tendency of recording engineers to hide the continuo, even on opera DVDs where the conductor is clearly seated at the harpsichord, sometimes with a second harpsichordist and theorbo player to boot. Only with the advent of the larger classical orchestra did the harpsichord become inaudible – hence Haydn's joke in giving it a prominent little part of its own at the end of Symphony No.98. we should be able to hear it, though not too prominently, in baroque music, especially when someone has gone to the trouble of writing out the continuo in Op.10 which Avison left incomplete.

Now I note that another review of these Avison Ensemble recordings has queried the comparative inaudibility of the harpsichord – and Divine Art have had the honesty to post the whole review on their web-page, not just the complimentary part. Thank goodness that I'm now not the only person to draw attention to the Emperor's new clothes. In fact, the continuo is intermittently audible on these recordings, but you have to listen hard for it and it's really no more prominent than on the ASMF modern-instrument recording of the Avison-Scarlatti concerti which I mention below.

Otherwise these concerti, though coming late in Avison's composing career, show little diminution of inventiveness from his Op.6 set and the Scarlatti and Geminiani adaptations. By the time that he wrote these works, their form would have sounded decidedly old-fashioned, in that they still evidently hark back to the music of Geminiani, who probably tutored Avison in London, and Geminiani's own model Corelli. There is just the occasional hint of the galant style but those who had heard the music of J C Bach, who was established in London seven years before the first of these concerti were published, must have thought this more like the music of JC's father. Avison was equally puzzled by the new-fangled; he wrote in the Newcastle Literary Register in 1769 that he wondered "where the powers of music are fled, not to harmonize the passions of men." What would he have thought if he had lived to hear Beethoven's late quartets?

We must not, however, berate him as stick-in-the-mud – I'm afraid you could call me that in respect of much music post-Schoenberg – but appreciate what he has to offer, which is a great deal indeed. As JV points out in his review of the Avison-Geminiani concertos, he was no mere clone of Geminiani or anyone else. The least that can be said of this music is that it is exceedingly well-crafted and often memorable. The notes in the booklet rather imply that Avison had gone off the boil a little by 1769, when he was 60. I didn't find it so – I think I'd passed my sell-by date at 60 far more than Avison.

These are excellent performances, preferably to be dipped into rather than heard complete: like JV, I found myself suffering from an excess of good things after listening to both CDs – and these two discs are more generously filled than the two which he heard. Those with an aversion to period instruments need have no fear: there are no raw or rough edges to the playing – if anything, I might have liked a little more of a feeling that the players weren't so adept as to make it all sound easy; I'm sure it isn't. With tasteful ornamentation where appropriate and a willingness to give the music a bit of a lift, these are excellent performances, just a little brighter than the ASMF on that Ace of Diamonds recording or on the Philips Duo listed below.

Apart from the near-inaudibility of the continuo, the recording is excellent. I found a slight reduction from my normal listening volume to be beneficial, otherwise the Ensemble sounds a little larger than the modest proportions listed in the booklet.

The notes by Simon Fleming are helpful and informative. The members of the Ensemble are individually named and details given of the period instruments or copies which they play. I wish all record companies were as forthcoming as this: I recently found it difficult to be sure that a particular orchestra played modern instruments, albeit with a sense of period style, when their label, Dynamic, failed to make this clear.

If these performances lead you to wish to explore Avison further, you could do much worse than the other Divine Art recording which I have mentioned – and their web-site announces that they are planning to offer his complete works by the end of 2009. Several Divine Art recordings should be available to download from Chandos's theclassicalshop.net, but the links there lead to the ‘unavailable' page. The Avison-Geminiani concertos are available from eMusic but, with a total of 43 tracks, they would make a very large hole in any monthly allocation and cost almost as much as buying the CDs direct from Divine Art. The iTunes price is even more expensive than buying the CDs, when Divine Art currently offer this set as a two-for-one bargain.

Otherwise, try the Naxos Op.6 recording first. Alternatively, since Avison was such a master of arranging the sonatas of Italian composers as concerti grossi, as the Geminiani set shows, you may wish to see what he made of twelve of Domenico Scarlatti's sonatas. Mark Sealey confidently recommended the Hyperion reissue of the performances by The Brandenburg Consort on the two-for-one Dyad label (CDD22060) The Philips Duo version of these appears to have been deleted, very serviceable performances from ASMF/Neville Marriner – remainders would be well worth looking out for (438 806-2) or perhaps Australian Eloquence will oblige with a reissue. Those who prefer modern instruments will find the ASMF almost as lively and stylish in this music as their period-instrument competitors – just a little too rounded and ‘comfortable'.

Don't forget the music of Avison's contemporary, William Boyce, which I also got to know first from that Neville Marriner Ace of Diamonds LP. You could do much worse than start with the Aradia Ensemble under Kevin Mallon on Naxos 8.557278, though I note that Jonathan Woolf thought this second-best to the mid-price AAM/Hogwood recording (473 081 2/

And if you want to hear the music of the next generation, try the Chichester Concert, whose Olympia recording of five symphonies by John Marsh, written in the 1770s, has just been reissued at super-budget price by Alto. These are accomplished performances on copies of period instruments – I shall certainly be buying the Alto reissue of their recording (ALC1017), since my copy of the Olympia has developed an unfortunate repeating groove.

I understand that these two well-filled Divine Art CDs are being offered for the price of one – an additional incentive, if one were required, to obtain them. That would make them eligible for nomination as Bargain of the Month, but I have another candidate in mind as a possible for that title.