reviews

reviews

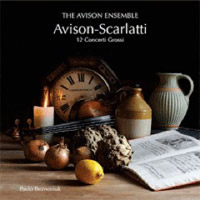

Charles Avison

12 Concerti Grossi after Scarlatti

The Avison Ensemble

Pavlo Beznosiuk (director & violin)

Pavlo Beznosiuk (director & violin)

2 CDs on Divine Arts, dda 21213

• BBC Radio 3 Essential CD of the Week, 7 - 11 November 2011 •

Classic FM Magazine

'... the real trump card is the quality with which they're played here .'

Malcolm Hayes

A fine exploration of Avison's under-explored legacy and his masterful reworkings of Domenico Scarlatti's existing works.

In the unlikely surroundings of 18th century Newcastle, local musical entrepreneur Charles Avison made a name for himself with his Baroque string concertos, including this collection based on existing works (some of them now lost) by Italy's Domenico Scarlatti. While rather short-changing the fiery vibrancy of Scarlatti's brilliant harpsichord writing, Avison's arrangements and re-workings are never less than engaging and stylish. However, the real trump card is the quality with which they're played here. Under leader-director Pavlo Beznosiuk, springy rhythms combine with a lovely pliable way with the music's pacing and phrasing.

ClassicalNet

'Each concerto is a joy to listen ... Beznosiuk directs these works with consummate panache ...'

Gerald Fenech

This delightful two disc set is a welcome addition to the catalogue where these concertos have been sparsely represented of late. After having tackled similar works for Divine Art, the Avison Ensemble now lend their talented vein to these Scarlatti arrangements by their namesake composer and the result is quite enthralling.

Each concerto is a joy to listen to and although the music is brought together from other works, there is an innate feel that everything is complete and should be "there". Pavlo Beznosiuk directs these works with consummate panache and his violin playing is also impeccable as can be expected from this old warhorse of this sort of repertoire. He is also ably supported by his players who are also seasoned campaigners in such music.

Divine Art's presentation is as usual, impeccable with detailed and informative notes and an excellent recording to boot. I am keen for more music from this source, perhaps some Geminiani or Corelli which are also quite under-represented in the repertoire and which would benefit from such a fine approach.

Musicweb (1)

'These are fine, loving performances ... there is understanding and affectionate respect in all that they do with the music.'

Glyn Pursglove

There are fine booklet notes to this very enjoyable pair of CDs. They are by Simon D.I. Fleming, who reminds us that English interest in the music of Domenico Scarlatti was largely a product of the encounter between Thomas Roseingrave and the composer, in Venice , around 1710. The Irishman Roseingrave brought copies of some of Scarlatti's works back to Britain, was responsible for the 1720 London production of Scarlatti's opera Amor d'un'ombra (as Narciso ) and, in 1739 published his edition of Scarlatti's Essercizi as XLII Suites de Pieces Pour Le Clavecin .

One early English admirer of Scarlatti's work was Charles Avison. In 1743 he published a single Concerto in Seven Parts done from the Lessons of Sig r Domenico Scarlatti , a publication sufficiently well-received to encourage the publication in the following year of the set of twelve concertos recorded here.

In his Essay on Musical Expression , first published in London in 1752, Avison included a footnote on Domenico Scarlatti (my quotation is taken from the third edition of 1775, p.46), who he describes as 'the author of some excellent lessons for the harpsichord '. He praises him as 'among the great masters of this age', going on to add that 'the invention of his subjects or airs , and the beautiful chain of modulation in all these pieces , are peculiarly his own: and though in many places, the finest passages are greatly disguised with capricious divisions , yet, upon the whole, they are original and masterly'.

In his adaptations of Scarlatti's keyboard works as materials for a set of concertos, Avison operates precisely with that mingled air of admiration and reservation he expresses in the passage just quoted. The very nature of the exercise registers his delight in Scarlatti's music; but the freedom with which he treats his source, adjusting tempi here and there (often quite considerably), rewriting harmonies and adding (and omitting) material also suggests a composer who doesn't feel confined by the work of an admired predecessor.

Most of the movements in these concertos are based on individual sonatas by Scarlatti, their combination into four movement sequences being entirely Avison's work. Sometimes sonatas are transposed; some movements (nine in total, out of forty eight) have no identified source and may be Avison's own work. They stand up to the comparison with Scarlatti very well.

These are fine, loving performances. The slower movements have an attractive lyricism, the faster ones have a crisply rhythmic quality - though I wouldn't have minded hearing the continuo section a bit more prominently. Particular pleasures include the effervescent Allegro and dignified Largo from Concerto No.4 - the largo being one of the movements with no identified source in Scarlatti - and the expressive Andante Moderato from Concerto No.11 which is one of the best of the group when heard whole.

Pavlo Beznosiuk and his ensemble have done the memory of Charles Avison great service with these and other recordings. There is understanding and affectionate respect in all that they do with the music.

International Record Review

'... the playing is uniformly superb throughout; this latest release is no exception.'

Robert Levett

Charles Avison (1709-1770) apparently studied with Francesco Geminiani in London before being appointed organist at St. Nicholas's. Newcastle; he later organised a series of subscription concerts in both Newcastle and Durham. Apart from being a prolific composer of mainly instrumental works, he also wrote on music, his most significant publication in that area being the Essay on Musical Expression (1752).

Apart from writing his own concerti grossi, Avison arranged for that genre Corelli's Op. 5 and Geminiani's Op. 1 sets, both originally for violin and basso continuo, as well as a number of the keyboard sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti, whose music had become known in England thanks to the efforts of Thomas Roseingrave, who had met the Italian composer in Venice. Avison's set of 12 Concertos after Scarlatti was published in 1744.

The excellent Avison Ensemble under the directorship of violinist Pavlo Beznosiuk has already recorded Avison's 18 Concerti Grossi, Opp. 9 and 10 and 12 Concerti Grossi after Geminiani for Divine Art, as well as Avison's Opp. 3, 4 and 6 sets for Naxos. I have yet to hear the Opp. 9 and 10 recording, but for the rest I can say that the playing is uniformly superb throughout; this latest release is no exception.

Avison has used four sonatas for each concerto, forming a typical slow-fast-slaw-fast pattern; his concertino mostly comprises two violins, of which the second player here is uncredited (Joanne Green, perhaps, - the first of the five named violinists in the ensemble after Beznosiuk). There have also been some transpositions and slight alterations, but by and large these are faithful transcriptions of the keyboard originals. The results, especially in performances of this calibre, are such that the listener is able more fully to comprehend the character of each sonata to the extent that he or she returns to the originals with fresh ears – surely the measure of success of any good transcription or arrangement. I especially enjoyed the joyful exuberance of KK13 in Concerto no. 2, the Vivaldian Kk37 of No. 3, the stately KK88 of No. 7 and the beautiful amoroso of No. 8.

Apart from the solo work, the ripieno strings together with the harpsichord continuo provide not only solid support but often demonstrate real independence in accordance with Scarlatti's original writing, though never at the expense of tightness of ensemble. The recorded sound is excellent. Simon D. I. Fleming's booklet notes provide much useful information on the genesis and reception of these fascinating and colourful works.

Musicweb (2)

'A thoroughly enjoyable and technically first class recording of the Twelve Concerti Grossi ...'

Jonathan Woolf

A review of this thoroughly enjoyable and technically first class recording of the Twelve Concerti Grossi has already appeared on this site, written by Brian Wilson. He went into some detail regarding the origin of the work and also relating the provenance of the movements derived from Scarlatti. As he says, Divine Art makes all this crystal clear in its booklet notes, fine ones by the way, as is by now usual.

I'm going to concentrate instead on the many virtues of both music and performance and to recommend once again this fast rising ensemble. Beznosiuk has been a leading original instrument practitioner for a good long while now and his experience in the repertory and his direction of The Avison Ensemble is evident at every turn.

Each Concerto Grosso is cast in four movements, of the standard slow-fast-slow-fast kind. From the A major, which starts the set one is aware of the lithe sonority cultivated by the ensemble, of the interplay between the strings and the two violin concertino and of the well balanced weight throughout – the orchestra is 6-2-2-1 with the harpsichord played by Roger Hamilton. There is also warmth, as one can feel in the Amoroso of the same A major work. Where definition is required it duly appears, as in the etched bass line of the Allegro of No.2 and where Avison asks for spiritoso , as he does in the Allegro second movement of the D minor [No.3] we find the ensemble more than happy to meet the request.

The Allegro of No.4 in A minor fizzes by – it's taken from the sonata Kk3 – and is laced with the kind of wit that Beznosiuk so readily finds in the music. The ensuing Largo is stately – Avison is good at touches of pomposo – whereas the opening Largo of No.5 is quite dramatic. Michael Nyman should get his hands on it. These kinds of pleasures and virtues abound in this two CD set. The wistfully withdrawn Siciliana of No.9 and the affecting Andante moderato of No.11 in G major are equally supple and delightful. And note too the daring dynamics cultivated by Beznosiuk and the ensemble in the finale of No.12 or the exciting and biting verve cultivated in the same Concerto Grosso's second movement.

In short this is another fine exploration of Avison's under explored legacy. The ensemble that bears his name does him further honour in this excellently recorded survey.

The Consort

'This is exemplary baroque string playing, and at its most tasteful.'

Ibrahim Azin

Charles Avison (1709-70) was one of the 18th century figures who helped to promote Domenico Scarlatti's keyboard compositions in England. He did this through his arrangements of a selection of Scarlatti's works, partly gleaned from Thomas Roseingrave's edition of the former's pieces issued in London in 1739 and from an earlier publication of 1738. From these, as well as from various other manuscript sources, Avison compiled and arranged about fifty movements of Scarlatti and grouped them into twelve concerti grossi for strings and continuo. These were published in 1743 and 1744. By this time Avison had become an established musical figure in the northeast of England, having built his reputation in the 1730s in London, where he was said to have studied under Geminiani. It was also in London that he attracted lucrative offers of posts in Dublin, Edinburgh and York, the latter as organist at York Minster. He turned down all of these in order to return to his native Newcastle in 1736, taking up positions at the churches of St John and St Nicholas, where he remained until his death in 1770.

Avison wrote a great deal of instrumental music, much of it published, mostly in the traditional Italian style of Corelli and Geminiani, but some in forms that were more adventurous for his time – there were, for example, keyboard sonatas with obbligato violins and cello, a forerunner of the classical piano trio of Haydn and Mozart, and also keyboard quartets employing the same configuration. He also composed a steady stream of concerti grossi from the 1740s until shortly before his death; during that time, Avison wrote a total of about fifty concerti, making him one of the most important 18 th century English composers in the genre. The Scarlatti arrangements seem to have been a successful venture, and Avison's subscription list, which included leading musical figures of the day such as Maurice Greene, James Nares and Avison's former teacher Geminiani, shows that his arrangements were at least well distributed.

Avison seems to have been a socially committed man: he taught, organised concerts and orchestras, had a great number of influential friends, wrote reviews, pamphlets, and subscribed to music – which was how he came across the Scarlatti pieces in the first place. In them he clearly saw something new and exciting, worth introducing to his audience and also, perhaps somewhat unashamedly, something that could be developed further. To his credit, Avison openly justified his treatment of these pieces, pointing out, as the CD test recounts, that ‘by forming them into Parts, and taking off the Mask which concealed their natural Beauty and Excellency, [this] will not only more effectually express that pleasing Air, and sweet Succession of Harmony, so peculiar to the Compositions of this Author, but render them more easy and familiar to the Instrument for which they were first intended'. By this means he encouraged the appreciation of the Scarlatti originals, and was able to popularize both the works and his own name at the same time.

So what do these concertos sound like? It was most interesting to listen to them. At times it felt as if I already knew the pieces quite well, and then the music would suddenly veer into another direction for a moment, before returning to the point from which it broke off, into more familiar territory. At other times it was barely recognisable – until I realised it was actually familiar music played at half speed! Sometimes the melody and tempo are Scarlatti's but the accompanying harmonies are fresh. It was reminiscent of piano lessons, of pieces that were learnt wrong and should have been played in another way. All this, of course, has to do with how Avison handled the original templates and adjusted them to suit his judgment and his personal taste.

Many listeners will be familiar with the original Scarlatti sonatas, and they may well react to the music as I did, but for those less familiar with Scarlatti, this may be a new and revealing experience. New because Avison is still – probably for many – a relatively recent acquaintance, and revealing because the musical arrangements are exceptionally well composed. As the CD booklet points out, composed. As the CD booklet points out, they were so crafted that ‘unless previously informed, one would never have realised that these pieces were not originally conceived as concertos'.

As with any arrangements, Avison's give us an insight into how he – an actual contemporary of Scarlatti's – viewed the latter's works and dealt with the raw materials laid before him. Avison's arrangements were widely known, given their long subscription list and the fact that they were referred to in various contemporary sources, most notably Laurence Sterne's The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy , but there is no evidence that they reached Scarlatti himself – it would have been interesting to know what he thought about them.

The Avison Ensemble, originally formed to champion the composer's works, is here represented by a dozen players, an ensemble close in size to that which Avison would probably have had in Newcastle in the mid 1700s. Pavlo Beznosiuk's exquisite and highly distinctive violin tone is finely balanced by a shimmering and polished string band, with precision and elegance being their obvious strengths. Pianissimo passages are a delight, as is the deftly executed, if at times slightly calculated, ornamentation, and the whole ensemble is sensitively supported throughout by a buoyant but gutsy continuo team. This is exemplary baroque string playing, and at its most tasteful.

This recording contains something for everybody – the Scarlatti enthusiast, the musicologist, the teacher and the student, as well as string and keyboard players. For me it offered a combination of nostalgia and surprises, a motivation both to revisit some neglected keyboard music and also to delve into more of the works of this composer whom Charles Burney referred to as ‘an ingenious and polished man, an elegant writer upon his art'.

Musicweb (3)

'This excellent pair of CDs ... the performances and recording are equally fine.'

Brian Wilson

This excellent pair of CDs follows hard on the heels of Divine Art's release of the Avison Ensemble's recording of their eponymous composer's Opp. 9 and 10 Concertos (DDA 21211), which I so recently recommended – see review. If anything, this is finer music than those concertos – hardly surprising when the originals were sonatas by none other than Domenico Scarlatti – and the performances and recording are equally fine.

The London publication in 1739 of 42 Scarlatti sonatas provided Avison's inspiration in arranging movements from several of those as concerti grossi . His excuse, if one were needed, was the difficulty of performance of the music in its keyboard original state, but he couldn't help also preening himself on having "tak[en] off the Mask which concealed their natural Beauty and Expression". I beg leave not to get into the thorny question of the adequacy or otherwise of the originals – performances of the calibre of those of Richard Lester on his complete Nimbus cycle would suggest that there was little amiss – but the music certainly sounds more varied and probably more amenable to most modern ears in its orchestral dress. More recently, Tommasini had the same idea in his arrangement as a ballet for Diaghilev of Scarlatti's music in The Good-humoured Ladies .

Avison didn't orchestrate whole concertos; some, like No.1 are from just two sonatas (Kk91a/d and Kk24), others from four different originals, like No.2, from KK 91c, 13, 4 and 2. The Divine Art booklet makes the provenance of each movement clear, also indicating with an asterisk movements transposed to a different key, with a dagger where the movement has been shortened or altered, and with two asterisks where the source is unknown.

Most of those unknowns, mainly slow movements, were probably Avison's own compositions – sounding in no way out of place in the company of the Scarlatti-derived movements. Everything, original or not, is very skilfully arranged – preferable to the Sinfonie di Concerto Grosso of the elder Scarlatti, Alessandro, as least as performed, slightly heavily, by I Musici on Philips 400 017 2 – one of the first batch of CDs in 1983, but no longer available. (For all my reservations, this is worth reissuing, but there are alternatives on Tactus TCC661906 and 661907 and CPO 999 8562.)

Hitherto my benchmark recording has been that of the Academy of St Martin under Neville Marriner (Philips Duo 438 806-2, no longer available). It was, indeed, from the ASMF on a long-deleted Oiseau-Lyre LP that I first came across the music of Avison and his contemporary Boyce and discovered thereby that English music between Purcell and Elgar had not been quite the desert that it had been portrayed as.

This new recording is ample compensation for the deletion of the ASMF set. It doesn't exactly wipe the floor with the earlier version, which is still worth considering if you find it as a remainder or second-hand at a reasonable price. Surprisingly, some of the tempi on the new set are slightly broader than on the Philips. No.1/iv, for example, takes 4:43 at Beznosiuk's hands, 4:01 at Marriner's. On CD2, No.7/iv now takes 4:17 against Marriner's 3:33. I compared the two versions of these movements and found, as is often the case, that both make perfect sense in their own context. Perhaps I lean slightly to Marriner in 7/iv – he stresses the allegro part of the marking, Beznosiuk the affettuoso part – but I don't want to make a big issue of it.

I shall still want to hear the ASMF versions – I couldn't resist listening to the two CDs straight through for comparison – but the new versions are likely to make for more frequent listening. It's a tribute to the music and to both performances that I could listen to four well-filled CDs in one session without becoming sated.

The ASMF version employs modern instruments, though with cognisance of period practice; the Avison Ensemble employ period instruments, as itemised in the booklet. There is a rival period-performance from the Brandenburg Consort and Roy Goodman on Hyperion Dyad CDD22060 (2 CDs for the price of one). I haven't heard this version but it has been described in some quarters as likely to sound a little rough and ready to those not fully attuned to early instruments. Mark Sealey certainly didn't in general share that opinion in his review of this set, and I find it a little surprising in view of the excellence of their performances of the Handel Op.3 concertos which I have recommended here on Musicweb.

You certainly won't find anything of the sort about the playing of the Avison Ensemble on the new set – this is early music without the rough edges, by which I don't mean to imply that it's dull or over-polished: this isn't the early-music equivalent of the Berlin Phil under Karajan. I'm still hard put to hear the continuo, though, as I was with the earlier Op.9/10 set – I don't want to hear a monster harpsichord clattering away, but I'd like to hear a little more of it. Otherwise, the recorded sound is first-rate.

The Avison Ensemble have already recorded the music of their namesake for Naxos and Divine Art. Their 2-CD recording of the Concerti Grossi, Op. 6 on Naxos 8.557553-4 was welcomed by Jonathan Woolf and Johan van Veen as doing Avison proud – see JW's review and JV's review. Robert Hugill was equally appreciative of their later recording of Opp. 3 and 4 (8.557905-6 – see review ). I hope to include an appreciation of the Naxos recording of the Op.6 works in my November, 2008, Download Roundup: this is Avison's finest music with the possible exception of the Scarlatti-based concertos.

Having switched to the Divine Art label, the Ensemble recently recorded the newly-discovered set of Concertos after Geminiani's Op.1, to the satisfaction of JV again, though he had some reservations about the recorded sound – (DDA21210, see review). All these recordings are very worthy of your consideration but the Naxos Op.6 and the new Divine Art sets are probably the best places to start. With the new set offered at two-for-one, it's very little dearer than the Naxos, so why not get both?

The only black mark that I can place against this whole enterprise is the failure to provide Avison's dates, which is all the more surprising when Divine Art include such a wealth of detail about the provenance of each movement.

Listen (USA)

'The performances are beyond praise ... The intonation is impeccable, the pacing perfect; the balance is exemplary ...'

Edith Eisler

Charles Avison's Twelve Concerti Grossi after Scarlatti are more than mere transcriptions. By his own account, Avison took great liberties with the originals, convinced, despite his admiration for them, that they could be “improved by the removal of certain elements” and that “forming them into parts” would better reveal their “natural beauty”. Thus one cannot discern where Scarlatti leaves off and Avison begins. Scarlatti's music is utterly beautiful, and Avison's version brings out its qualities to best advantage.

To create the customary concerto format, Avison used four alternately slow and fast sonatas, he assembled them so skilfully that each concerto becomes a coherent whole. His transcriptions are remarkably idiomatic to the instruments. Among this cornucopia of treasures, listeners will find their own favorites, but no one will be able to resist the lyrical, deeply expressive melodies of the slow movements or the lilting rhythms of the dances.

The performances are beyond praise. The players use period instruments (listed along with their names) and semi-period style, with very little vibrato but a full, warm tone. The intonation is impeccable, the pacing perfect; the balance is exemplary with a strong, solid bass. The players create variety through articulation and dynamics, and are sensitive to every mood change and expressive nuance. Beznosiuk is a virtuoso violinist but acts as a first among equals, stepping forward and melting back into the ensemble seamlessly; when there are two soloists, they sound indistinguishable.

Fanfare (USA)

''The performances are lively and expert ... I would opt for The Avison Ensemble.'

Ron Salemi

The New Grove considers Charles Avison “the most important English concerto composer of the 18 th century.” He wrote 60 original concerti grossi, not counting the works on this recording, which were mostly arranged from keyboard sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti. Avison's creative life was centered on Newcastle, where, among other activities, he organized concerts similar to those of J. C. Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel in London during the same period.

In 1739, Thomas Roseingrave was responsible for introducing Domenico Scarlatti to a wider audience by his publication of an edition of 42 of Scarlatti's keyboard sonatas. Avison was impressed by these works, but he thought they could be improved by removing what he called “capricious Diversions, or an unnecessary Repetition in many Places.” He decided to arrange some of the sonatas in the form of concerti grossi of the chiesa form, in four movements, slow-fast-slow-fast. He was somewhat hampered by the fact that Roseingrave's publication contained little that was suitable for slow movements. However, Avison was able to acquire other sonatas in manuscript form, which helped him complete a set of 12 concertos. Ten movements, all slow ones, have not been identified and were probably composed by Avison.

The Avison Ensemble was formed following the discovery of a collection of Avison concertos. Its expressed aim is to “enhance public awareness of Avison and the many other neglected British composers of the baroque period.” For Naxos and Divine Art, the group has recorded Avison's concerti grossi opp. 3, 4, 6, 9, and 10, and his 12 concertos after Geminiani's op. 1 violin sonatas, as well as music of the English composers John Garth and William Herschel (the discoverer of the planet Uranus). The performances are lively and expert. Conductor Pavlo Beznosiuk adopts reasonable tempos that allow the music to make its point without exaggeration.

These works have been recorded complete at least twice before. A modern-instrument recording with Neville Mariner and the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields may never have been transferred to CD; it is, at any rate, not currently available. Roy Goodman recorded them with The Brandenburg Consort for Hyperion, and that set is still in the catalog. There is little to choose between the two recordings. Timings are nearly identical. The Brandenburg Consort is a slightly larger ensemble, with strings 5-5-3-2-1 vs. The Avison Ensemble's 3-3-2-2-1. The main difference between the two is the continuo instrumentation. The Avison Ensemble uses harpsichord throughout, which the Brandenburg Consort alternates organ and harpsichord and adds archlute, theorbo, or guitar to each movement.

While I would not call these pleasant works essential listening, they are worth an occasional hearing. I could be happy with either of the two available recordings, but if forced to choose, I would opt for The Avison Ensemble.

Allmusic

'Recommended for British music lovers and serious fans of the period, and nowhere less than pleasant for anyone else.'

James Manheim

This release, helmed by prolific Ukrainian-British violinist Pavlo Beznosiuk , might better be titled Scarlatti-Avison; the original music is by Domenico Scarlatti , as arranged by British composer Charles Avison just a few years after the fact. The eighteenth century was a time in which musical recycling, either by an original composer or by others, was an entirely acceptable practice, and the beginnings of the practice of reducing orchestral works for keyboard date from this period also.

Going from keyboard music to an orchestral version, however, was much more unusual at this time (a century later it too would be common enough), especially in the case of music so thoroughly conceived for the keyboard as Scarlatti 's. Avison wrote, perhaps defensively, that in Scarlatti 's original sonatas, "many delightful Passages...[have been] entirely disguised, either with capricious Diversions, or an unnecessary Repetition in many Places...." He goes on to claim that he has succeeded in "taking off the Mask which concealed their natural Beauty and Excellency." The listener by this time will be ready to object that it is the capricious diversions and unnecessary repetitions that make Scarlatti 's keyboard sonatas so much fun, but the word "natural" is key here; Avison , although he sticks generally closely to the source material, tries to purge it of its Baroque traits.

The result, perhaps more interesting for those immersed in the eighteenth century than for general listeners, is a little snapshot of changing tastes at a time when naturalness was emerging as the aesthetic value to be cherished most. Avison's shoehorning of Scarlatti's keyboard textures into the concerto grosso format (a concerto grosso is a concerto for a small group, known as a concertino, with a larger string orchestra) is ingenious, but he opts for simplicity and homogeneity over dramatic contrast wherever possible, and Beznosiuk's interpretations, with the handpicked Avison Ensemble, emphasize sweetness and smoothness. Recommended for British music lovers and serious fans of the period, and nowhere less than pleasant for anyone else.

BBC Music Magazine

'They are substantial pieces, earning lively and sensitive playing from the Ensemble's 11 strings and continuo.'

George Pratt (joint review with dda21211)

Charles Avison (1709-70) unusually made a considerable name for himself outside London – as writer, composer, concert promoter and organist. Although he spent time in the capital as a pupil of Geminiani, he returned to his birthplace, Newcastle, for the rest of his working life.

Avison wrote no less than seven full sets of concertos, choosing the older style and formal structure of Corelli and Geminiani – four movements and a trio of soloists – rather than the gallant Vivaldian three-movement model with virtuoso solos. As the basis of his 1744 set, he took the keyboard studies of Domenico Scarlatti, transcribing them into 12 effective orchestral concertos. We have Avison to thank for preserving ten of Scarlatti's movements, otherwise unknown. They are substantial pieces, earning lively and sensitive playing from the Ensemble's 11 strings and continuo. Scarlatti's invention makes them distinctive, and often memorable – the poignant opening of No. 3, the Con furia in No. 6 elicits some powerful playing especially from leader Pavlo Beznosiuk.

The later sets here are less striking and three-to-a-part upper strings have occasional raw movements. A pity, perhaps, that the Ensemble didn't take up Avison's commercially-inventive options: he described them as suitable for orchestra, or quarter or even solo harpsichord, to vary the textures. The over-riding impression after hearing 71 brief movements, many under a minute long, is of urbane charm, fluent melody and purposeful harmony, but no one concerto imprints itself on the memory for long. They are nonetheless attractive, now, as they were for audiences at Avison's regular subscription concerts in the Newcastle Assembly Rooms.

Musical Opinion

'... this eponymous ensemble is clearly made up of very gifted musicians whose corporate and individual artistry is impressive. Strongly recommended.'

Robert Matthew-Walker

This is the latest installment from Divine Art in their important series of recordings of music by the Northumbrian composer Charles Avison, a two CD set of twelve Concerti Grossi ‘after Scarlatti', first published in 1744. This is beautifully-crafted music, very much of its time (if not a little earlier in terms of style) and reminiscent of course, in certain passages, of not dissimilarly-intentioned works by Handel and William Boyce – in so far as the English orchestral school of the time is concerned.

Playing upon period instruments, or on modern copies thereof, this eponymous ensemble is clearly made up of very gifted musicians whose corporate and individual artistry is impressive. Pavlo Beznosiuk is the admirable leader/director, and I found listening to these discs a stimulating and rewarding experience. What did surprise me was that when confronted as critics are – by twelve Concerti Grossi one after another, each in four movements, they never fall into a repetitious mode; they are delightfully varied, with a fascinatingly wide range of expression; as a single example, the slow movement in No 2 in G major is a truly fascinating long study, and I was completely taken by the little No 8 in E minor and its companion No 10 in D.

The recording quality is consistently good, although some may feel the musicians are a shade too closely miked, and deserved a slightly fuller acoustic. The presentation is generally first-class except that the otherwise very good booklet note by Simon D.I. Fleming, whilst losing no opportunity to give the dates of just about every individual who is mentioned, omits to give us those by Avison himself! He lived from 1709-1770 but they are nowhere to be found in any part of the booklet or packaging.

But the music's the thing, and this issue is one that deserves wide success, for individual concertos, such as No 5 in D minor and NO 11 in G major; are remarkable examples not just of English music of the period – indeed, in such cases, of European music of the period. Strongly recommended.